Building peace, cohesion, and prosperous societies have often been assigned to education. However, as Bowles and Gintis (1976) put forward in Schooling in Capitalist America, there is a Correspondence between schooling and life: schooling mirrors opportunities in life. Systems, including schooling, reproduce class systems and perpetuate the status quo.

There are 3C’s in education: content, context, and culture.

The taught curriculum, content, is but one of the three factors that make the field of education. Under such circumstances, it is presumptuous to assume that a wholesome taught curriculum alone can create peace, cohesive, and prosperous societies.

Content

When discussing the issues related to education and its inability to promote peace and cohesion, however, the taught curriculum is the one that is at the forefront of the attack; and for good reason. The taught curriculum is the one C that is easiest to observe, and therefore criticise. It is also the only C that can be documented with little criticism of biasness. For instance, in 2011 Huffington Post accused textbooks in Texas of “injecting conservative ideals into social studies, history and economics lessons that will be taught to millions of students for the next decade.” Proof of textbooks in Texas altering history was numerous: there were instances where the atrocities of Ku Klux Klan were downplayed; they identified slaves as immigrant works distorting a significant portion of history. In Sri Lanka, the history textbooks in the 1970s and 1980s (at the early stages of the 30-year civil war) declared Tamils as the historic enemy of the Sinhalese. While this outright declaration was then taken out, the history textbooks are heavily biased towards the Sinhalese, noting the great work done by Sinhalese Kings. Tamils have been portrayed as the outsider residing in the country due to the benevolence of the Sinhalese. A crucial point that was highlighted by historians studying the history textbooks in Sri Lanka were the discrepancies between Sinhala-medium history book and the Tamil-medium history book. In the former, King Elara – a Tamil King – was presented as an invader who was defeated by arguably the most famous Sinhala King, Dutugamunu; in the latter, King Elara was presented as a just King who was beloved by the people. In Turkey, the Armenian issue was introduced to the school textbooks as “how the Armenian gangs operated and betrayed the Turks;” “the Armenian involvement in the insurgencies against the Ottoman government;” and “Armenians’ status according to the Treaty of Sevres”. Textbooks, whether in Texas or Sri Lanka or Turkey, are often written by the majority or those in power. Thus, there is more chance of distorting histories and shaping narratives to suit the majority ideology. However, addressing the issue of textbooks, i.e. content, does not guarantee peace or a prosperous society.

context

The second C in the three C’s is context, and this essay categorises pedagogy – through that, the teachers – as part of the context. Content may be created in a pluralistic fashion with input from multiple stakeholders. Yet, in the classroom, the context of the content is set by the teacher. It is futile to purge the content/the textbooks when the minds of the teachers, those who deliver the content, are not purged in the same fashion. As noted in the Texas example, many conservative teachers advocate for this version of history. In Sri Lanka, there are teachers, especially from the majoritarian ethnic group, Sinhalese, who strongly believe that providing a diverse/pluralistic narrative would harm unity and peace. In Turkey, the study noted that the teachers’ responses seem to be taken out of old textbooks and lacked authenticity. When the curriculum is presented as the perfect solution to social issues of peace and conflict, the advocates often forget that the textbook, or the taught curriculum, is often mediated by individuals in the classroom. i.e. teachers. These mediators are humans with their own ideas, ideologies, and to an extent, agendas. Thus, assuming that fixing the taught curriculum would fix the problem is a misinformed assumption. In fact, one of the criticisms of Correspondence theory noted above, is that it ignores the agency of the teachers and learners involved in the process (Cole, 1988). If these individual teachers can note the distortion in histories, they can easily counter the “pluralistic” taught curriculum to shape the minds of their learners. Thus, if there is to be peace, cohesion, and peaceful society, the context – the pedagogies, the teachers – has to be addressed and remedied, too.

CUlture

The third C refers to Culture – an abstract idea that has a significant impact on education. Culture is as much what is explicitly seen in the textbooks, in the classroom; what the teacher says; what the students say; as it is what is not said. Culture is both the loud voice that says what something is, and the silences that operate within it. Culture is present in the language choice, in the stylistics, and every other element of education. When culture is non-pluralistic, it permeates to other aspects of education, too. In the Texas example, culture is illustrated in a cartoon that ridicules affirmative action. It could be passed off as a joke; yet, it is illustrative of the underlying cultural notions of affirmative action. In the Sri Lankan example, culture is apparent in that Sinhala writers write the history curriculum and it is then translated to Tamil. Culture is also apparent in the way that the history of Sinhalese is presented as the history of Sri Lanka. It is not overt, but it exists. In the Turkey example, culture can be identified when the State created the us-vs-them narrative. Furthermore, culture is not something that can be bound within the borders of education. Culture is larger: from bigoted tweets of President Trump to presidential press releases being released only in Sinhala in Sri Lanka, culture is created. It then seeps into education, colouring both context and content. Due to this pervading nature of culture, until it promotes peace, cohesion, and prosperous society, it is unlikely that content – taught curriculum – alone can achieve much.

***

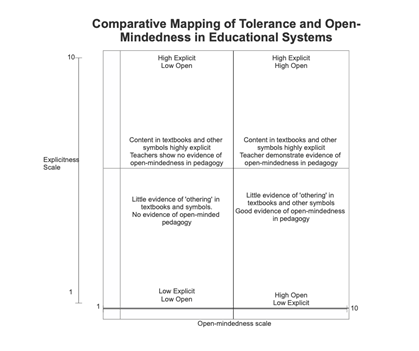

As depicted in the following scale by Johnson, two axes come together to determine the nature of an education system. Content is part of the explicitness scale, while context and culture belong to the open-mindedness scale. Therefore even if there is “little evidence of othering in textbooks and symbols”, if the open-mindedness scale is at the lower end, it cannot support a prosperous society.

The taught curriculum can, most certainly, aid the building of peace, cohesion, and prosperous society. However, the taught curriculum alone can do little for the sustainable and effective building of peace and cohesion. It is the easiest place to start, though, due to its tangible and observable nature. Its effectiveness, however, is determined by the teachers, the students, and the cultural context of the society. Therefore, while the taught curriculum cannot be a sole champion, it can and should serve as one pillar for building peace, cohesion, and prosperous society.